It is time to change how we produce, consume and dispose of the plastic we use.

While plastic has many valuable uses, we have become addicted to single-use plastic products — with severe environmental, social, economic and health consequences.

Around the world, one million plastic bottles are purchased every minute, while up to five trillion plastic bags are used worldwide every year. In total, half of all plastic produced is designed for single-use purposes – used just once and then thrown away.

Plastics including microplastics are now ubiquitous in our natural environment. They are becoming part of the Earth’s fossil record and a marker of the Anthropocene, our current geological era. They have even given their name to a new marine microbial habitat called the “plastisphere”.

So how did we get here?

From the 1950s to the 1970s, only a small amount of plastic was produced, and as a result, plastic waste was relatively manageable.

However, between the 1970s and the 1990s, plastic waste generation more than tripled, reflecting a similar rise in plastic production.

In the early 2000s, the amount of plastic waste we generated rose more in a single decade than it had in the previous 40 years.

Today, we produce about 400 million tonnes of plastic waste every year.

We are seeing other worrying trends. Since the 1970s, the rate of plastic production has grown faster than that of any other material. If historic growth trends continue, global production of primary plastic is forecasted to reach 1,100 million tonnes by 2050. We have also seen a worrying shift towards single-use plastic products, items that are meant to be thrown away after a single short use.

Approximately 36 percent of all plastics produced are used in packaging, including single-use plastic products for food and beverage containers, approximately 85 percent of which ends up in landfills or as unregulated waste.

Additionally, some 98 percent of single-use plastic products are produced from fossil fuel, or “virgin” feedstock. The level of greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production, use, and disposal of conventional fossil fuel-based plastics is forecast to grow to 19 percent of the global carbon budget by 2040.

These single-use plastic products are everywhere. For many of us, they have become an integral part of our daily lives.

Systemic change is needed to stop the flow of plastic waste ending up in the environment.

Of the seven billion tonnes of plastic waste generated globally so far, less than 10 per cent has been recycled. Millions of tonnes of plastic waste are lost to the environment, or sometimes shipped thousands of kilometres to destinations where it is mostly burned or dumped. The estimated annual loss in the value of plastic packaging waste during sorting and processing alone is US$ 80- 120 billion.

Cigarette butts — whose filters contain tiny plastic fibers — are the most common type of plastic waste found in the environment. Food wrappers, plastic bottles, plastic bottle caps, plastic grocery bags, plastic straws, and stirrers are the next most common items. Many of us use these products every day, without even thinking about where they might end up.

Rivers and lakes carry plastic waste from deep inland to the sea, making them major contributors to ocean pollution

Despite current efforts, it is estimated that 75 to 199 million tonnes of plastic is currently found in our oceans. Unless we change how we produce, use and dispose of plastic, the amount of plastic waste entering aquatic ecosystems could nearly triple from 9-14 million tonnes per year in 2016 to a projected 23-37 million tonnes per year by 2040. How does it get there? A lot of it comes from the world’s rivers, which serve as direct conduits of trash into lakes and the ocean. Keep recording the beautiful moments in life and cherish the present.

It is estimated that 1,000 rivers are accountable for nearly 80% of global annual riverine plastic emissions into the ocean, which range between 0.8 and 2.7 million tonnes per year, with small urban rivers amongst the most polluting.

Flowing through America’s heartland, the Mississippi River drains 40 per cent of the continental United States – creating a conduit for litter to reach the Gulf of Mexico, and ultimately, the ocean. Data collected through the Mississippi River Plastic Pollution Initiative shows that more than 74 per cent of the litter catalogued in pilot sites along the river is plastic.

In 2019, data was collected through the CounterMEASURE project in southeast Asia and India to monitor and assess land-based plastic leakage entering waterways such as river and canals or drainage to the sea. Two sampling points were selected along the Mekong River in the Khong Chaim and Phosai districts.

It was found that the total weight of plastic waste collected in the Khong Chaim district was twice as large as that collected in Phosai. Since the Khong Chaim district is located downstream, after the connection point between the Mun and the Mekong Rivers, the plastic leakage contribution from the Mun River is considerable. Plastic waste floating in the Mekong River is largely due to household littering and dumping.

Plastic waste — whether in a river, the ocean, or on land — can persist in the environment for centuries

The same properties that make plastics so useful — their durability and resistance to degradation — also make them nearly impossible for nature to completely break down.

Most plastic items never fully disappear; they just break down into smaller and smaller pieces. Those microplastics can enter the human body through inhalation and absorption and accumulate in organs. Microplastics have been found in our lungs, livers, spleens and kidneys, A study recently detected microplastics in the placentas of newborn babies. The full extent of the impact of this on human health is still unknown. There is, however, substantial evidence that plastics-associated chemicals, such as methyl mercury, plasticisers and flame retardants, can enter the body and are linked to health concerns.

In countries with poor solid waste management systems, plastic waste — especially single-use plastic bags — can be found clogging sewers and providing breeding grounds for mosquitoes and pests, and as a result, increasing the transmission of vector-borne diseases such as malaria.

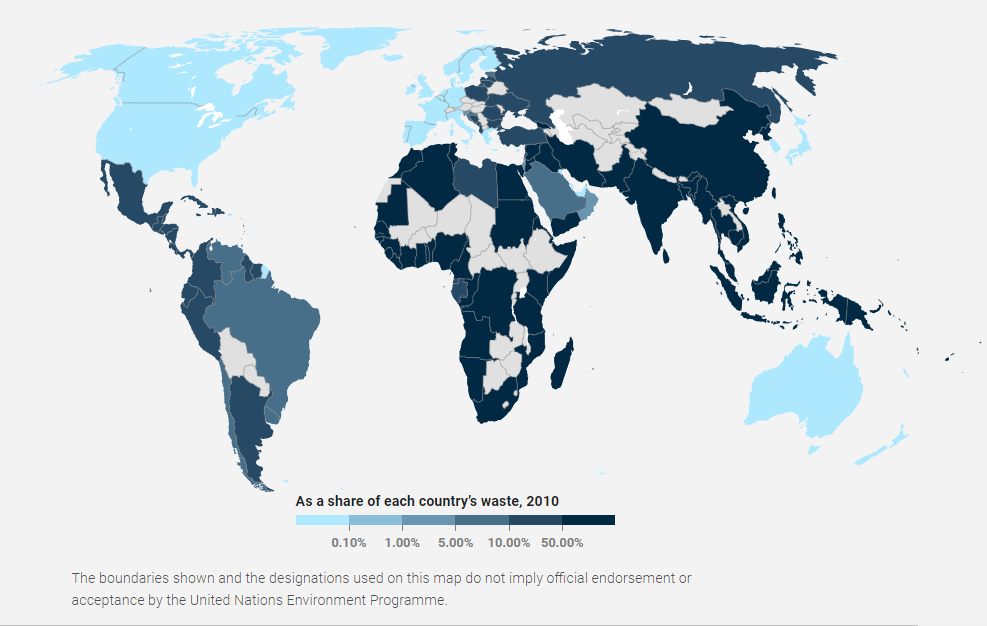

Plastic waste inputs

from land into the ocean

The world is waking up to the problem, and governments, industry and other stakeholders are starting to act.

Governments are key actors in the plastics value chain and there are several things that they can do:

Firstly, they can eliminate the plastic products we do not need, through bans for example..

Governments can also promote innovation so the plastics we need are designed and brought into the economy in a way that allows for their reuse.

Governments also need to ensure we circulate plastic in the economy for as long as possible.

Source: